Edward Said

From Geography

JikkeVanTHof (Talk | contribs) (→Postcolonialism) |

JikkeVanTHof (Talk | contribs) (→References) |

||

| Line 57: | Line 57: | ||

-Gregory, D. (2000). Edward Said’s imaginative geographies. In Mike Crang and Nigel Thrift (eds.) Thinking space. Routledge, London, pp.302-348. | -Gregory, D. (2000). Edward Said’s imaginative geographies. In Mike Crang and Nigel Thrift (eds.) Thinking space. Routledge, London, pp.302-348. | ||

| - | - | + | -Gregory, D. (2000). Decolonising Geography: Postcolonial Perspectives. Chapter 5 in: Blunt, A. & Wills, J. (eds.) ''Dissident Geographies: an introduction to radical Ideas and Practice''. Prentice Hall, London. |

-Gregory, D., Johnston, R., Pratt, G., Watts, M. J., Whatmore, S., (2009). Dictonary of Human Geography 5th edition. Wiley-Blackwell. | -Gregory, D., Johnston, R., Pratt, G., Watts, M. J., Whatmore, S., (2009). Dictonary of Human Geography 5th edition. Wiley-Blackwell. | ||

| + | |||

| + | -Said, E.W., (1978). Orientalism. London: Penguin. | ||

-Said, E. W. (1994). Culture and Imperialism. London: Vintage. | -Said, E. W. (1994). Culture and Imperialism. London: Vintage. | ||

Revision as of 09:30, 14 October 2011

Contents |

Biography

Identity- who we are, where we come from, what we are- is difficult to maintain in exile...we are the 'other', an opposite, a flaw in the geometry of resettlement, an exodus. Silence and discretion veil the hurt, slow the body searches, soothe the sting of loss (Said, E., 1986 in Ashcroft & Ahluwalia, 2001, p.3)

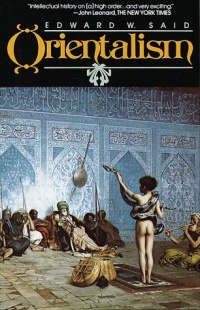

This quotation illustrates the life of Edward Said [1] (1 November 1935- 25 September 2003), which was a very well known and often recited Palestinian-American critic, political commentator and literary and cultural theorist, which could be placed within postcolonialism. He was born in 1935 in Jerusalem, Palestine. By that time, Palestine was under British administration. After the second World War, Edward Said and his family went to Cairo. Said didn't really feel comfortable living in Cairo, and after he was expelled from highschool in 1951, his parents sent him to the United States. In America, it wasn't that easy either, but Said was very clever: he graduated at Princeton University, went to Harvard for his Ph.D and became an Assistant Professor of Comparative Literature at Columbia University, New York. Untill than, he maintained two identities: as a Palestinian and as an American. But "the 1967 [Arab-Israeli] war and its reception in America confronted Said with the paradox of his own position; he could no longer maintain two identities, and the experience began to be reflected everywhere in his work (...) he began to construct himself as a Palestinian" (Ashcroft & Ahluwalia, 2001, p.3). This quotation shows Said's struggle with his identity and his politicisation after the Arab-Israeli war, which have had a major influence on his important works Orientalism (1978), The Question of Palestine (1979) and Covering Islam (1981). Orientalism could be seen as his most influental and most recited work, which will be discussed here as well. The most important thing that can be concluded from Said's biography, is that his own life has been very crucial to the direction of his theory. As Ashcrof and Ahluwalia (2001) say: "The condition of his own life, the text of his identity, are constantly woven into and form the defining context for all his writing. His struggles with his dislocation, his recognition of the empowering potential of exile, his constant engagement with the link between textuality and the world, underlie the major directions ofo his theory and help to explain his uncertain relationship with contemporary theory" (p.5)

Postcolonialism

As said above, Said can be placed within the postcolonial tradition. This tradition is in itself very diverse, but a common idea is that postcolonial thinkers are in fact anti-colonial (Gregory, in Blunt and Wills, 2000, p. 167). Postcolonial theory is very well explained by Ashcroft and Ahluwalia (2001). The theory is focussed on investigating "the cultural and political impact of European conquest upon colonised societies, and the nature of those societies' responses" (p. 15). The post in the term postcolonialism doesn't mean that we really reached an era after colonialism, because there are still many effects visible of the colonial period and "the cultural struggles between imperial and dominated societies continue into the present" (p. 15). Gregory (in Blunt and Wills, 2000) marks that "[a]lthough the formal structures of colonial rule might have been overturned, the legacies of colonial rule remain intact in many spheres of life both in metropolitan centres and in ex-colonies. The political, administrative, legal, educational and religious systems in many ex-colonies continue to reflect past European colonial influence"(p. 178). The main focus op postcolonial theory are the cultural influences of European conquest and their recent consequences and the responses of the colonized societies.

Part of the postcolonial theory is 'colonial discourse analysis', which critically studies colonial discourses, "the apparatus of power that legitimates colonial rule over people and places at distance" (Gregory, in Blunt and Wills, 2000, p. 181). Said's work Colonialism, which will be discussed in the next section, can be seen as a very important work in which colonial discourse analyses has a central role.

Key ideas

Several key ideas can be distinguished throughout Said's work.

Orientalism

Imaginative geography

The term or the idea of an imginative geography was first mentioned by Edward Said in 1975 in his critique of orientalism. In his view the imaginative geography consits of a triangulation of power, knowledge and geography. He deploys the term imaginative geography to capture the connective imperative between geography and discourse within the unequal framework of empire: the ‘dramatisation’ of difference between ‘us’ and ‘them’, and ‘here’ and ‘there’, with texts ‘creat(ing) not only knowledge but also the very reality they appear to describe’ (Dictionary of Human Geography, 2009). By this he meant that the meaning or the perception of a specific place is created by the dominance of the most powerful authority. He refered to the colonial power of the Northern society which created and shaped a particular stereotyp of foreign countries. He describes landscapes and cultures as beeing drawn into abstract grids of colonial and imperial power, literally displaced and replaced, and illuminates the ways in which these constellations become sites of appropriation, domination and contestation (Gregory, 2000). This means that in contrast to other behavioural geographies where the cognition plays a main role, imaginative geography, because it is a cultural construct, is also influenced by imagination, desire and the unwitting, automatic idea of a place or thing. Through the creation of images of different places and the representation of places through images and tales, the places are enriched with a particular value. As a result the feeling of `otherness´ and `us´ and `them´ arises. So what Said wanted to say is that through the circulation of images, texts and narrartives a certain world is created and through the continious use and circulation of this images a certain sence of authority is created.

As a good example the `war on terror´ could be mentioned. There is also a form of imaginative geography to be recognized. By talking and downgrading the Afghan society as enemies who are attacking the northern civilization a specific image is created and brought around the world until many people take it as a fact.

Culture as imperialism: contrapuntal reading

Said says that you can't look at imperialism without looking at culture. Ashcroft and Ahluwalia (2001) say about this: "the role of culture in keeping imperialism intact cannot be overestimated, because it is through culture that the assumption of the 'divine right' of imperial powers to rule is vigorously and authoritatively supported" (p. 85).

Contrapuntal reading

By reading contrapuntally you take in to account intertwined histories and perspectives. No one account is privileged, and Said used this to analyse and interpret colonial texts as he considered both the view of the colonized and the colonizer. Said is interpreting in a contrapuntal manner, interpreted the different perspectives simultaneously and tried to see how they related. It is reading with "awareness both of the metropolitan history that is narrated and of those other histories against which (and together with which) the dominating discourse acts" (Said, 1994). The concept of contrapuntality was first used by Said in the essay Reflections on Exile and was further developed in Culture and Imperialism.

Said was influenced to read contrapuntally through his love of western music, especially piano, which he played. Contrapuntal music combines two different parts of music that will result in a nice sound. Thus reading contrapuntally will take two different perspectives together and come up with an idea of a relationship between the two. So: "Contrapuntal reading takes both (or all) dimensions of this polyphony into account, rather than the dominant one, in order to discover what a univocal reading might conceal about the political worldliness of the canonical text" (Ashcroft & Ahluwalia, 2001, p. 93).

Geography

Robbins (in Ashcroft & Ahluwalia, 2001) says that "Said's own sense of the contrapuntal process is that it is a way of 'rethinking geography'" (p. 94). Ashcroft and Ahluwalia (2001) note that "[r]ather than just another way of reading the text, contrapuntal reading uncovers the geographical reality of imperialism and its profound material effects upon a large proportion of the globe"(p. 94). So, its about the struggle over geography. Said (1994) says about the struggle over geography that "[j]ust as none of us is outside or beyond geography, non of us is completely free from the struggle over geography. That struggle is complex and interesting, because it is not only about soldiers and cannons but also about ideas, about forms, about images and imaginings"(p.6).

Area of overlap with the Action-Theoretical tradition

Area of divergence with the Action-Theoretical tradition

Critique

References

-Ashcroft, B. and Ahluwalia, P. (2001). Edward Said. New York, London: Routledge.

-Gregory, D. (2000). Edward Said’s imaginative geographies. In Mike Crang and Nigel Thrift (eds.) Thinking space. Routledge, London, pp.302-348.

-Gregory, D. (2000). Decolonising Geography: Postcolonial Perspectives. Chapter 5 in: Blunt, A. & Wills, J. (eds.) Dissident Geographies: an introduction to radical Ideas and Practice. Prentice Hall, London.

-Gregory, D., Johnston, R., Pratt, G., Watts, M. J., Whatmore, S., (2009). Dictonary of Human Geography 5th edition. Wiley-Blackwell.

-Said, E.W., (1978). Orientalism. London: Penguin.

-Said, E. W. (1994). Culture and Imperialism. London: Vintage.

Contributors

-Biography edited by --JikkeVanTHof 12:06, 29 September 2011 (UTC)

-Imaginative geography edited by --FabianBusch 12:07, 04 October 2011 (UTC)

-Contrapuntal reading edited by --SamanthaHazlett 14:52, 6 October 2011 (UTC)

-Images inserted and page updated by --JikkeVanTHof 16:26, 13 October 2011 (CEST)

-Contrapuntal reading enhanced by --JikkeVanTHof 10:58, 14 October 2011 (CEST)